The man who controls 1.4 billion lives

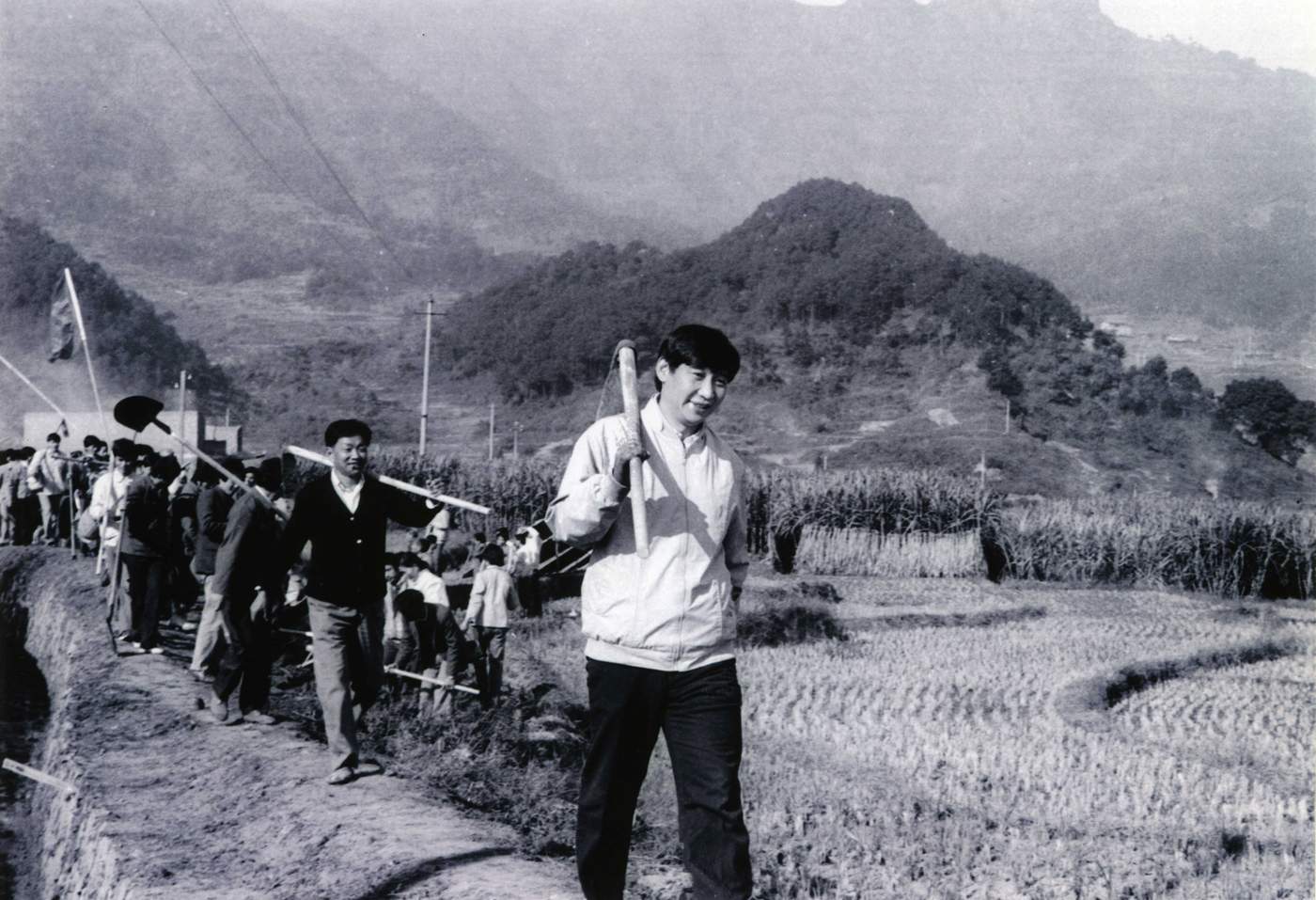

There aren’t many 21st Century leaders who lived in a cave and laboured as a farmer before clawing their way to power.

Five decades ago, as the chaos of the Cultural Revolution engulfed Beijing, the 15-year-old Xi Jinping embarked on a harsh rural life amid the yellow canyons and mountains of inland China.

The region where Xi farmed was a bastion of the Communists during the civil war. Yan’an came to call itself “the holy land of the Chinese revolution”.

Now President Xi Jinping’s second five-year term as leader will be confirmed at the Chinese Communist Party Congress. He leads a confident, rising superpower, but one which jealously polices what is said about its leaders.

Xi’s own story has been sanitised and while much of rural China has seen breakneck urbanisation, the village where he grew up is now a pilgrimage destination for the Communist Party faithful.

In 1968 Mao had decreed that millions of young people should move from the cities to the countryside to learn from the hard life of the peasants.

Xi says he did learn, and that the ideas and qualities which define him today were formed in his early cave life. “I’m forever a son of the yellow earth,” he likes to say. “I left my heart in Liangjiahe. Liangjiahe made me.

“When I arrived at 15, I was anxious and confused. When I left at 22, my life goals were firm and I was filled with confidence.”

df

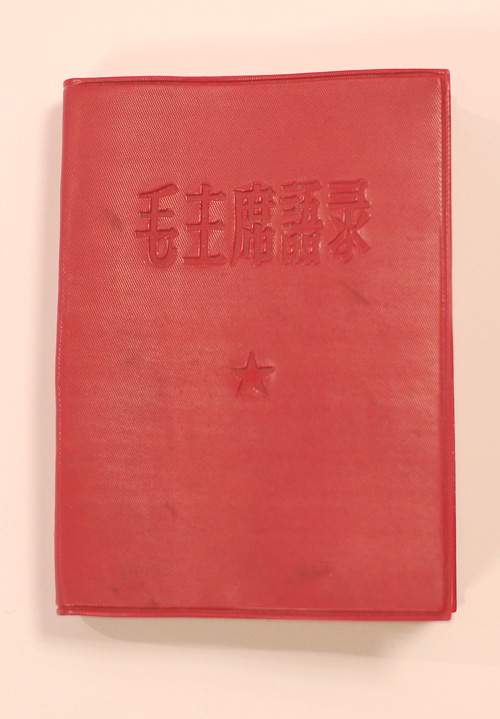

Back then everyone studied Chairman Mao’s famous little red book. Now the thoughts of Chairman Xi are posted on huge red hoardings and there is a museum in his honour. It extols the good deeds he did for his fellow villagers but all trace of true personality has been expunged in a story so saintly it is hard to work out what is real.

In his first five years in office, Xi Jinping has built a personality cult. At its core is the image of a man of the people. He has toured back-alley homes, ducking through washing lines. He has talked in earthy prose, telling students that life is like a shirt with buttons where you have to get the first few right or all the rest will be wrong. He has queued in a downmarket steamed-bun shop and paid for his own lunch.

But it is his early exile from home and family, a political outcast in a cave, that is the heart of Xi’s creation myth.

“People who have little experience with power… tend to regard it as mysterious and novel. But I look past the superficial things - the power and the flowers and the glory and the applause. I see the detention houses, the fickleness of human relationships. I understand politics on a deeper level.”

The young Xi had already lived two lives by the time he arrived in the cave. During his early childhood, his father was a hero of the communist revolution and Xi enjoyed a privileged and cloistered upbringing as a “red princeling”.

The young Xi Jinping (left) with his younger brother and their father

A 2009 American diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks - and based on a briefing from a close friend of Xi’s - said the first 10 years of his life were the most formative.

“The most permanent influences shaping Xi's worldview were his ‘princeling’ pedigree and time growing up with families of first-generation Communist Party revolutionaries in Beijing's exclusive residential compounds.”

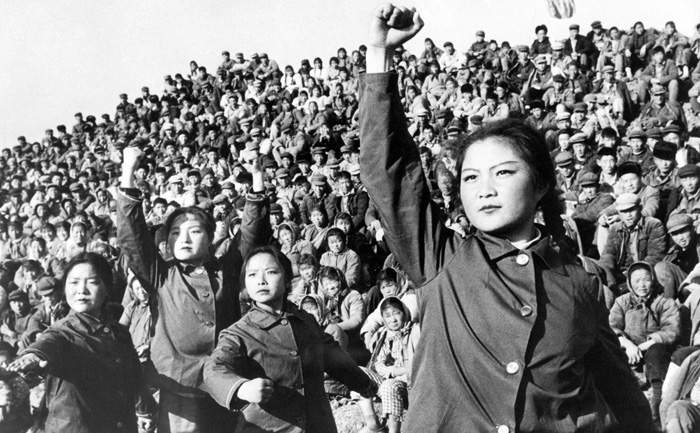

But all of that was shattered in the maelstrom that an increasingly paranoid and vengeful Chairman Mao inflicted on the party elite in the 1960s. Xi’s father was first purged and then jailed, and his family humiliated. One of his sisters died, possibly driven to suicide. By the time he was 13, Xi’s formal schooling ended as classes across Beijing were suspended so that students could criticise, beat and even murder their teachers.

1966: Chinese Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution

Without parents or friends to protect him from the Red Guards dispensing the summary justice of the Cultural Revolution on the streets, the teenage Xi lived his second Beijing life, dodging death threats and detention. Much later, he recalled an encounter in a conversation with a reporter.

“I was only 14. The Red Guards asked, ‘How serious do you yourself think your crimes are?’

“I said, ‘You can estimate it yourselves. Is it enough to execute me?’

“‘We can execute you a hundred times,’ they replied.

“To my mind there was no difference between being executed a hundred times or once.”

Comments

Post a Comment